Reflections on EMNLP 2024

I presented two papers at EMNLP: one about multilingual NLP and one about tokenization. So, a lot of the conversations I had centered around those topics, but not all of them! I wanted to just reflect on some of the cool papers I saw and some of the interesting conversations I had.

Multilinguality and Low-Resource Languages

I presented our paper, “When Is Multilinguality a Curse? Language Modeling for 250 High- and Low-Resource Languages” on the first day of the conference. At the poster I had some interesting discussions. The most frequently asked question at the poster was about how the results will generalize to larger models, since the biggest models we trained were 45M parameters. I think it’s hard to know, since this paper was the first paper to try to do a controlled study pretraining models from scratch with different combinations of languages (at least first to include such a wide range of languages). It would be incredibly expensive to run these experiments with larger models, and I don’t think it would be worth it. But one of the takeaways from the paper is that if you have a single target language for which you want to optimize performance, and you have enough data to train a model, I would not rule out the value of training a monolingual model – even if it means training a smaller model. In a follow-up paper, we showed that even a monolingual 100M parameter model can beat XGLM 4.5B, because of how small the proportions of training data are for some of the low-resource languages.

Another big takeaway from the paper is that we should question the role of English as the default language to include in a multilingual model. For example, if you wanted to train a state-of-the-art Korean language model, the mainstream approach would be to use all the data you can find for Korean and then supplement it with English data until you have enough to train your model. This is motivated by the fact that the most, the best-quality, and the most diverse datasets are in English. Also, if you want any domain-specific data, it probably (mostly) is in English. But the results from our paper would suggest that including data from more closely related languages would lead to more benefits from crosslingual transfer.

One question people had was what combination of languages should they include in order to improve performance, especially for a language with a very small amount of data available. To take Korean as an example, we found that syntactic similarity was the best predictor of benefitting from added multilingual data, as calculated with the syntactic similarity metric calculated using lang2vec. Because Korean is a language isolate (i.e. it has no other members in its language family), the most similar languages would be be languages like Turkish or Mongolian1.

Unfortunately, because the poster sessions are arranged by topic, I didn’t get to see the other posters about multilingual NLP. I was sad to miss related work, like Targeted Multilingual Adaptation for Low-resource Language Families and Breaking the Curse of Multilinguality with Cross-lingual Expert Language Models.

On Wednesday, multilingual NLP – at least how bad the current state of it is – was highlighted in the panel “The Importance of NLP in the LLM Era”. First, Alice Oh acknowledged how bad language model performance is for low resource languages:

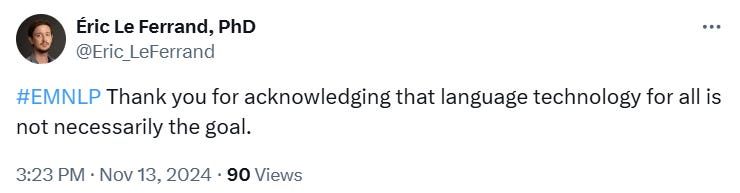

And then she implied that it hasn’t necessarily been a goal of the field to make language models work well for all languages.

Multilingual NLP is usually seen as a niche of NLP, rather than a research area that seeks to widen the applicability of NLP to more people. Success for language technologies has to mean technologies that work well for all languages. Otherwise, the field is just doing English Processing. I would really like to see *CL venues have more public discussions of this in keynotes and panels.

Last on the topic of multilinguality, I really liked the paper, “The Zeno’s Paradox of ‘Low-Resource’ Languages.” This paper contends with what it means for a language to be classified as low-resource, and how our framing of languages as high- or low-resource is damaging, as it changes the way researchers and language community members think about a language. I also really liked the point about how framing low-resource languages as having to catch up to high-resource languages, and especially English, will mean that we always understand progress for research and tools for low-resource languages as being less developed than for high-resource languages. I hope to use some of the points in this paper to change the language I use when talking about low-resource languages, primarily to be more precise by what I mean by that term.

Tokenization

Tokenization is not really the most popular topic in NLP, but there were quite a few interesting papers on tokenization. Marco Cognetta put together a great thread with all of them on BlueSky:

I presented our paper, “BPE Gets Picky: Efficient Vocabulary Refinement During Tokenizer Training” on the final day of the main conference. One of the topics of discussion at the poster was the issue of how we evaluate tokenizers. The paper “Tokenization Is More Than Compression” discusses how one of the most widely used metrics, compression, isn’t that predictive of the influence of a tokenizer on downstream performance. I think this is a huge problem that needs to be addressed before we can really expect to identify an ideal tokenization strategy.

I also really liked “Fishing for Magikarp: Automatically Detecting Under-trained Tokens in Large Language Models”, which was actually very closely related to the paper we presented. I think Sander Land, the first author of that paper, has done some amazing work to help show how important understanding the tokenizer, especially as it relates to hallucinations and model safety. I recommend looking at some of the glitch tokens the authors identified, which are easily viewable on their GitHub.

Sander also has a Substack, where he has some really interesting thoughts about the Claude 3 Tokenizer and pretokenization. The case of the Claude tokenizer is interesting, because it’s one of the only big closed models for which the tokenizer has not been released. This has led some people to speculate about why Anthropic have been so secretive about it:

In Sander’s blog post, he speculates about some of the features of the tokenizer based on API calls for Anthropic’s token counter.

Sander also has a very interesting post about pretokenization. Some of the regex rules in the GPT-4 tokenizer, which was re-used for the Llama models, break in some very unexpected ways. I also wrote a blog post a few months ago about pretokenization, where I talk about some of the reasons why re-using tokenizers from other models is a really bad idea.

Wrapping up

EMNLP was huge this year, with 3,400 in-person attendees. I found it really hard to see everything I wanted to see and meet everyone I wanted to meet. But, as usual, I walk away full of ideas and excited about a lot of cool things that other people are working on!

I’m not saying this in support of Altaic theory, necessarily.